“…with zeal and with bayonets only, it was resolved to follow Greene’s army to the end of the world.” –Brigadier General Charles O’Hara, Commander of the Brigade of Guards, 1781.

In the combat zones of the 21st Century one can find a dizzying array of weaponry, from ballistic missiles to barrel bombs, assault rifles to rocket launchers, hand grenades to IEDs, drones to chemical agents. If you were to inspect the kit of a soldier in any one of the many conflicts scattered around the world, chances are that in the midst of the GPS units, radios, and high-capacity magazines you will find a relic from an earlier time: the bayonet.

The bayonet had its origin in the early days of firearms. Early muzzle-loading weapons were slow to fire and unreliable. Infantry formations in those days often consisted of musketeers and pikemen: the pikemen, wielding their long spears, would keep enemy infantry or cavalry from overrunning the musketeers after the first volley. While firearms technology improved, the musket’s rate of fire remained too low to prevent a determined enemy from closing to within arm’s reach. “If only there was a way to turn those long, sturdy muskets into spears!” Enter the bayonet.

Early bayonets had a plug the owner shoved in the muzzle of his firearm, making the weapon incapable of firing until the soldier could spend some quality time getting it out. The technology evolved to include rings and sockets. By the time of the American Revolution the state of the art bayonet had a socket to secure it securely to the muzzle of the firearm, and business end consisting of a spike-like blade, around a foot-and-a-half long. The weapon could be loaded and fired with bayonet fixed, although it tended to get in the way of loading, slowing the process down slightly.

Throughout history soldiers have found many household uses for the bayonet: tent peg, candlestick holder, cooking spit, probe (I have personally used a bayonet to search the occasional haystack-it can be used to search for landmines, but that is not recommended), etc. While it can be helpful around camp, the bayonet is, at its heart, a weapon. It arguably reached its zenith as a weapon of war during the American War for Independence.

The British forces in American were quick to take stock of their enemy once the war broke out. American troops, especially militia, were handy with firearms. Given a prepared defensive position, such as the breastwork on Breed’s Hill in the battle that became known as Bunker Hill, the Americans would stand their ground and pour devastating volleys into the best troops the British could muster. They were not so tenacious, however, when faced with the bayonet’s “cold steel.” Many of the American troops, particularly the militia, finished their own firearms, which they used for hunting and other household chores; hunting weapons did not come with bayonets. Thus, few of the militiamen on Breed’s Hill were so equipped; when American ammunition ran low, the British surged forward, leading with the tips of their bayonets, and the Americans ran for it. That lesson was certainly not lost on the British.

After the evacuation of Boston the British retrained and adjusted their tactics in response to the lessons of 1775. Starting in the summer of 1776 the British would attack in open order, with space between men. They would not stop to trade volleys with the Americans. Instead, the British infantry would minimize its exposure to American fire by jogging or running toward the American positions. They might stop once to fire a single volley, but then would charge in with bayonets. This played out in the Battle of Long Island with several American positions being quickly overwhelmed by British and Hessian bayonet charges.

Needless to say, this presented quite a problem for the Americans. The solution involved organization, logistics, training, and leadership.

George Washington quickly realized that the militia was a “broken reed,” and that he would have to rely on a long-service, regular army along European lines. This regular, “Continental” Army, would be as uniformly equipped as possible; ideally each regiment would be equipped with a single model of military-grade musket, each with a bayonet. Once equipped, troops were trained in bayonet combat, giving them the confidence to face down their adversaries. The final ingredient was tactical leaders who knew how and when to employ the cold steel.

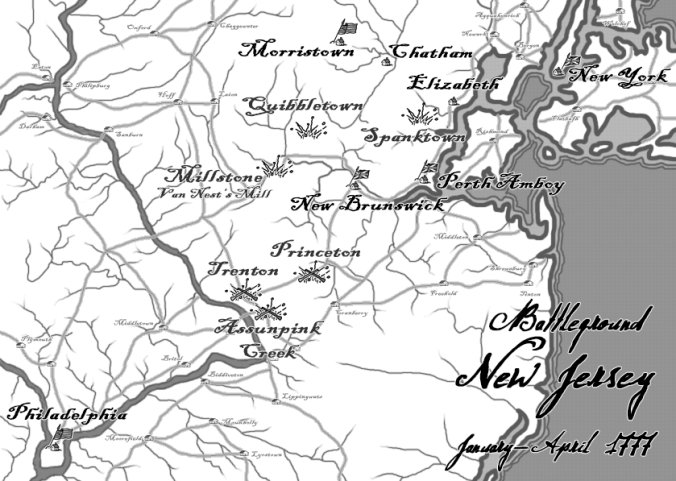

These reforms paid dividends. In the skirmish at Drake’s Farm, in February, 1777, (retold in my book A Nest of Hornets)Colonel Charles Scott and his 5th Regiment of Virginia Continentals were ambushed by a British Brigade. Rather than stand fast and allow his men to be pounded by artillery and encircled by enemy infantry, Colonel Scott led his men in a bayonet charge that broke a British grenadier battalion. This threw his enemy into confusion and bought Scott time to conduct a fighting withdrawal. At Saratoga, in September and October, 1777, Continental brigades not only held their ground against British regulars, but also launched several successful bayonet charges (A Constant Thunder). At Cowpens, in January, 1781, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan took advantage of British aggressiveness: he had his men feign retreat, and then turn, fire, and launch a bayonet charge against the exhausted British, winning the day and effectively destroying the entire British force. In the climactic act of the war, at Yorktown, In October, 1781, Redoubts 9 and 10 were carried by Franco-American nighttime bayonet charges.

These reforms paid dividends. In the skirmish at Drake’s Farm, in February, 1777, (retold in my book A Nest of Hornets)Colonel Charles Scott and his 5th Regiment of Virginia Continentals were ambushed by a British Brigade. Rather than stand fast and allow his men to be pounded by artillery and encircled by enemy infantry, Colonel Scott led his men in a bayonet charge that broke a British grenadier battalion. This threw his enemy into confusion and bought Scott time to conduct a fighting withdrawal. At Saratoga, in September and October, 1777, Continental brigades not only held their ground against British regulars, but also launched several successful bayonet charges (A Constant Thunder). At Cowpens, in January, 1781, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan took advantage of British aggressiveness: he had his men feign retreat, and then turn, fire, and launch a bayonet charge against the exhausted British, winning the day and effectively destroying the entire British force. In the climactic act of the war, at Yorktown, In October, 1781, Redoubts 9 and 10 were carried by Franco-American nighttime bayonet charges.

When the British landed on Long Island in the summer of 1776, they were convinced that they prod the Americans back into obedience to the Crown with the tips of their bayonets. Five long years later, the drama would culminate with French and American bayonets hemming in a British army at Yorktown. In future American wars the bayonet would be put to use: it would be wielded to great effect at places like Chapultepec, Little Round Top, the Argonne forest, and Iwo Jima. But perhaps never before or since the American Revolution were a war and a weapon so inextricably linked.

Robert Krenzel Facebook Author Page: https://www.facebook.com/RobertKrenzelAuthor/

Gideon Hawke Novels Facebook Page: https://m.facebook.com/GideonHawkeNovels/

Not that the material is not there! There is the almost mythical winter at Valley Forge, the “rebirth” of the Continental Army, the shockwaves caused by the French entry into the war (and the subsequent British strategic realignment), the British evacuation of Philadelphia, and the ensuing clash at Monmouth Courthouse (also steeped in myth and legend).

Not that the material is not there! There is the almost mythical winter at Valley Forge, the “rebirth” of the Continental Army, the shockwaves caused by the French entry into the war (and the subsequent British strategic realignment), the British evacuation of Philadelphia, and the ensuing clash at Monmouth Courthouse (also steeped in myth and legend). organization. It lacked the polish and uniformity of its foes, but it made the most of what it had. So it was at Valley Forge: the Continental Army endured an unpleasant winter, and it suffered at various times from shortages of food and supplies, but it was still a veteran force that made the most of what was at hand. Yes, Baron von Steuben lent a hand in training it, but would have trained without him. Had von Steuben, in his red coat, been clapped in irons upon arrival in America (as he almost was), I don’t think it would have changed the outcome at Monmouth…the Continental Army would have stood and fought stubbornly. Perhaps von Steuben gave the Continentals a bit more confidence, but I think his real contribution came later in the form of the standardized policies and procedures that made amateurs into professionals.

organization. It lacked the polish and uniformity of its foes, but it made the most of what it had. So it was at Valley Forge: the Continental Army endured an unpleasant winter, and it suffered at various times from shortages of food and supplies, but it was still a veteran force that made the most of what was at hand. Yes, Baron von Steuben lent a hand in training it, but would have trained without him. Had von Steuben, in his red coat, been clapped in irons upon arrival in America (as he almost was), I don’t think it would have changed the outcome at Monmouth…the Continental Army would have stood and fought stubbornly. Perhaps von Steuben gave the Continentals a bit more confidence, but I think his real contribution came later in the form of the standardized policies and procedures that made amateurs into professionals. Yesterday I had the opportunity to discuss the Gideon Hawke Series with the 8th Grade and Mill Creek Middle School in Lenexa, Kansas.

Yesterday I had the opportunity to discuss the Gideon Hawke Series with the 8th Grade and Mill Creek Middle School in Lenexa, Kansas. Fortunately, science had progressed to the point that scientists had been able to predict the event, and rather than be seen as an omen of good or evil, the eclipse was greeted with indifference by the troops. Perhaps, at best, the moon delivered some much welcome shade to deliver the troops momentarily from the brutal summer heat.

Fortunately, science had progressed to the point that scientists had been able to predict the event, and rather than be seen as an omen of good or evil, the eclipse was greeted with indifference by the troops. Perhaps, at best, the moon delivered some much welcome shade to deliver the troops momentarily from the brutal summer heat.

Regardless of how different society may have been in the 1770s to 1780s, people were still people, and war was still war. The human body reacted to danger and near-death in essentially the same way. So, when people in the 1770s and 1780s were exposed to trauma, many exhibited symptoms of would today be labeled PTS: insomnia, nightmares, nervousness, hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal issues, substance abuse, hearing voices, suicide, and so on. There were other manifestations which are less common today. For example, soldiers who had killed enemy combatants in hand-to-hand combat sometimes reported seeing the “ghosts” of their vanquished foes. But many of the symptoms would be very familiar to a modern combat veteran. Whatever the symptoms, science had not yet come to terms with PTS, and had not made the link between, for example, a soldier’s honorable service and behavior that could be viewed as bizarre if not frightening. The closest contemporary science may have come was applying the term “nostalgia” to this condition; it implied a link to homesickness, and did nothing to help those suffering from PTS.

Regardless of how different society may have been in the 1770s to 1780s, people were still people, and war was still war. The human body reacted to danger and near-death in essentially the same way. So, when people in the 1770s and 1780s were exposed to trauma, many exhibited symptoms of would today be labeled PTS: insomnia, nightmares, nervousness, hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal issues, substance abuse, hearing voices, suicide, and so on. There were other manifestations which are less common today. For example, soldiers who had killed enemy combatants in hand-to-hand combat sometimes reported seeing the “ghosts” of their vanquished foes. But many of the symptoms would be very familiar to a modern combat veteran. Whatever the symptoms, science had not yet come to terms with PTS, and had not made the link between, for example, a soldier’s honorable service and behavior that could be viewed as bizarre if not frightening. The closest contemporary science may have come was applying the term “nostalgia” to this condition; it implied a link to homesickness, and did nothing to help those suffering from PTS.