Is that a ghost? The thing seemed to be both dead and alive at the same time. Under normal circumstances neither word would apply to a small stone farmhouse, but here and now, they seemed most appropriate. The building looked dead because its charred interior, greyish walls, and the gaping windows and doors made it look alarmingly like a human skull. It looked alive because the two windows, the eye sockets, seemed to stare menacingly at passersby; especially passersby with guilty consciences.

Should we feel guilty? The captain wondered as he stared back at the house. Certainly his men had not set this particular house aflame, but how many others had they burned as they pursued the retreating rebel army? There had been many houses like this, each one home to a family, and each family had protested their innocence. None of them, they claimed, were sympathetic to the rebellion. Not that it had mattered. His men, along with so many others, had driven the families out, taken what valuables they could carry, rounded up the livestock, and laughed as the flames destroyed the families’ hopes and dreams.

There had been so much screaming and crying! Many of these Americans had gone too far in their protests, and earned themselves a smash from a musket butt or a thrust from a bayonet. It was harsh. It was terrible. But it was war. Now these Americans had learned the awful price of rising up against their God-given King: slaughter and desolation are the fruits of rebellion.

The captain shuddered against the wind. The dark gray sky and bare trees mirrored his bleak mood. It’s not the bone-chilling cold that’s so bad, he thought, nor is it the mind-numbing weariness. It’s not the fierce hunger pangs. Nor is it the fear of sudden death, or the pervading sense of doom. It’s all of those things combined! That’s what I hate about this miserable country!

The journey from their home in the principality of Waldeck last summer had been a nightmare; the captain had never sailed on the ocean before, and he had really thought the constant sea sickness would kill him. It had taken him and his men weeks to recover their strength in the stifling heat and humidity of Staten Island.

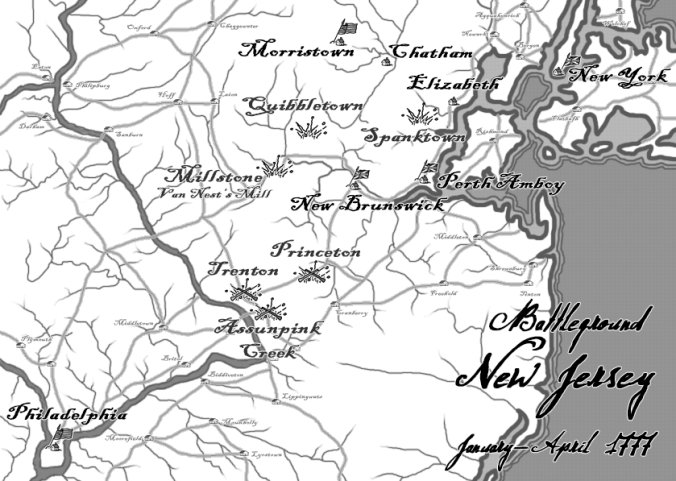

But once they actually started fighting the American scoundrels it had seem this war would turn into something of a lark; every time they grappled with the rebels, the discipline of the sturdy German troops had won the day, and the foe had fled the field. They had chased the Americans off of Long Island, off of Manhattan Island, and into the Jerseys. Here in New Jersey they were finally able to treat the population the way they deserved: brutally. In their wake the armies left almost nothing to sustain the rebellious population through this harsh winter.

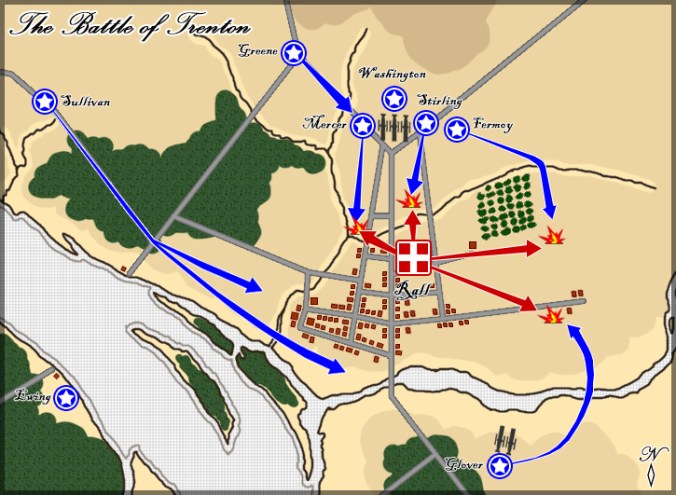

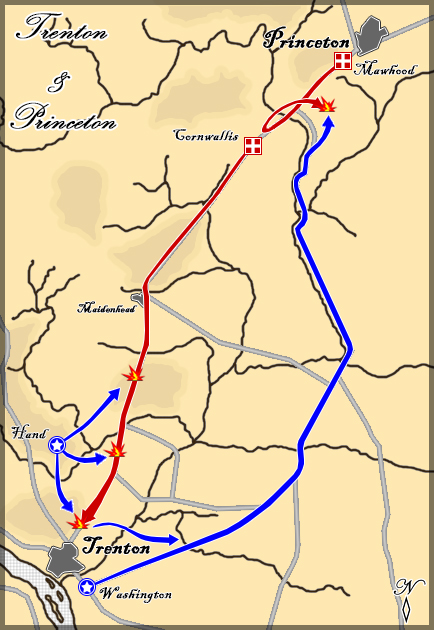

Unfortunately, that same devastation was now the biggest problem facing the British command. The plan had been to disperse the armies across the province and leave responsibility for foraging to the local garrison commanders. That would have been so simple! The captain wondered, Who could have foreseen this? Washington’s Army had seemed on the verge of collapse! How had that old fox managed to scrape together enough troops to go on the offensive? In less than two weeks he had crossed the Delaware, captured the Hessian garrison at Trenton, given the British the slip, returned to Trenton, humbugged his British pursuers, and shattered the British garrison at Princeton. Now it seemed that the Allied generals had panicked, pulling all of the British and German garrisons back into a small area in New York and Northern New Jersey.

Unfortunately, the men were now packed so tightly they couldn’t sustain themselves, and because the armies had done such a fine job devastating the New Jersey countryside that they were now having a devil of a time finding enough supplies to survive the winter.

As if the lack of provender were not enough, the Jersey militia had been delighted to see the British and Germans on the run; they been active in November and December, but the news of Trenton and Princeton had made them astonishingly bold! The lack of lodging meant his men had to sleep on the bare ground, and that was uncomfortable, but because of the constant alarms they had to do so fully clothed every night, with their weapons close at hand, ready to turn out at a moment’s notice in the event of militia attack. The men were subsisting on little but salted pork. That was depressing but manageable. The horses, unfortunately, needed fodder, and that had to be acquired from the nearly barren local countryside. That was why they were on the march today.

The captain and his fifty men, plus a dozen British light dragoons, were marching to chase away any militia and seize anything that might serve as horse fodder. With any luck they might catch a local farmer unawares and snatch a bit of fresh meat on the hoof; that would be a wonderful bonus!

The captain’s thoughts returned to the melancholy farmhouse. We are certainly not going to get anything from this farm. Where once animals had grazed and a family had eked out its living, now nothing stirred except a bit of snow drifting in the winter wind. All the while the farmhouse maintained its vengeful gaze.

The captain tore his eyes away from the building and looked ahead, toward the troop of dragoons about a quarter mile in front of his infantry. The road here crossed open fields, the stubble of a crop poking through the frost and snow marking what was once cultivated land. The fields were hemmed in on each side by gray, desolate woods. A low stone wall no more than waist-high bounded the field to the front of the horsemen. Beyond the fence was more barren forest.

POP! The captain sat upright on his horse. POP! POP! Musketry! The dragoons wheeled about in the field as puffs of smoke appeared along the wall in front of them. A few of the horse troopers fired from the saddle. What’s happening up there?

The captain spurred his horse forward and before long was up among the dragoons. Their lieutenant asked for permission to retire. Very well. Your task here is done for now. Soon the horsemen were dropping back, and the enemy fire faded away. The captain was now alone in the middle of the field. To his front, near the road, he could see about a dozen American militiamen in civilian clothes skulking behind the stone wall. From about a hundred yards away the rabble seemed immensely pleased with themselves for having driven off the horsemen. The enemy seemed to have no intention of retiring; they must not have seen the infantry yet. Excellent! The men will relish the chance to give this rebel scum the bayonet!

As the dragoons trotted rearward the infantry company deployed into a double line, in open order. The men moved smartly. The captain waited patiently, immobile, while the lieutenants and sergeants kept the men moving forward. They marched steadily, in cadenced step, closing the distance to the rebels. As the company neared the captain urged his horse forward, leading the men on toward the fight.

Once again shots rang out from the fence, and a few balls whistled by harmlessly. The rebels still showed no sign of running. Good! This will be over quickly!

The rebels worked feverishly to reload their muskets and fire at the advancing Waldeckers. The captain was not sure whether to admire or pity such foolish courage. At about seventy-five yards the captain halted his men, dressed their line, and ordered them to fix bayonets. That done, the relentless advance continued. This is too easy! The men might not even have to dirty their muskets by firing! A glance over his shoulder confirmed the dragoons were following behind the infantry, ready to take up the pursuit when the rebels broke and ran. Everything is in place!

The captain was gauging the distance. They were getting very close, almost within fifty yards. The militia had stopped firing; a few finished reloading their muskets. They were so close he could make out the smug, confident look on the enemy’s faces. They were clearly not afraid. What is that about? Why aren’t they frightened? Are they drunk? Don’t they realize we outnumber them almost five-to-one? Or do they know something I don’t?

Just then one of the twelve Americans let out a shout. Almost as one, about a hundred American militiamen rose from behind the stone wall. The captain froze, his mouth agape. It seemed to him that time slowed to a crawl. In perfect unison the rebels made ready and leveled their muskets. Then a wave of flame and smoke erupted from their line, and dozens of lead balls smashed their way through the company.

The first volley snapped the Waldeckers into action. The officers and sergeants started barking orders. Miraculously none of the leaders were down, but several of the men were sprawled on the ground or staggering rearward. As they had trained to do so often, and had done in earnest on several occasions, sergeants yelled and shoved to get the men to quickly close the gaps in the line. In no time the company was trading volleys with the militia. His men were much faster at loading and firing, but were hindered by the bayonets fixed to their muzzles. They were also fully exposed. In contrast the militia had the advantages of numbers and the stone wall. The wall would make the difference; over time more rebels than Waldeckers would survive the exchange. It was simply a matter of mathematics. A quick glance at his line told the captain that his company was in mortal danger. He has led them right into a trap, but perhaps a bayonet charge would save the day. Perhaps, just perhaps, one quick rush would break the Americans or at least buy him time to…ZIP—THUD!

The captain felt as though he had been punched in the gut. I’ve been shot! He felt the wound and then stared at the blood on his gloved hand. One of the lieutenants rode up and asked if he was badly hurt. Should I hand over command? Another ZIP was followed by a CRACK, and the lieutenant fell from his horse with a gaping hole in the side of his head. Something caught the captain’s eye, and he looked up at the forest off to the right flank of his company. There, about a hundred yards away, a puff of smoke! ZIP—THUD! Another bullet slammed into the captain’s thigh. Rifles! He hadn’t considered that. The captain took a last glimpse at what was left of his company. Half of the sergeants had fallen, and the hidden riflemen were singling out the rest. Nearly leaderless, the men who could still do so started running for their lives. Good, maybe some of them will escape. As his command disintegrated, the captain slid off his horse and fell in a heap on the iron hard ground. That should have hurt, but I hardly felt it! I must be in a bad way.

The captain was distracted by figures rushing by. He struggled to make sense of what he was hearing and seeing. He snatched a moment of clarity: the figures were American militiamen chasing his infantrymen. Run lads, run! Get away from these people!

The captain tried to rise, but collapsed back onto the ground. I am so tired. He laid on his back, rested his head on the ground, and gazed at the steely gray clouds, low in the sky overhead; the clouds reminded him of Waldeck. It’s strange how we can be so far away from home, but have the same clouds overhead. Suddenly his view of the sky was blocked by a wide-brimmed hat. Confused, the captain focused on the form looming over him. It took a moment to make out the face staring down at him. It was an American provincial, squatting over him, leaning on a musket. “Well, you’re clearly not British, are you?” the man asked, “German?”

The captain nodded weekly. His English was not so good, but he managed to follow as the man went on.

“Well, Mister German,” the American said with a grin, “Wilkommen in New Jersey!”

This short story started as a prologue for Gideon Hawke #3, A Nest of Hornets.

In the 1700s there was no highway system in the United States, and all-season roads were a rarity. The fastest and most efficient way to move people and goods was often by water. Commerce flowed up and down rivers, and ferries traversed the larger rivers to connect what road networks existed on either side. The British rightly considered the New England states to be the birthplace of the Revolution, and the theory was that if they could isolate New England from the rest of the rebellious former colonies, they might be able to concentrate their forces and stamp out the rebellion piecemeal. At the very least, establishing a cordon around New England might have forced George Washington into attacking to break the cordon. Given superior British discipline, firepower, and potentially numbers, such a battle might well have led to the destruction of Washington’s main force; in that event American capitulation would likely have been merely a matter of time.

In the 1700s there was no highway system in the United States, and all-season roads were a rarity. The fastest and most efficient way to move people and goods was often by water. Commerce flowed up and down rivers, and ferries traversed the larger rivers to connect what road networks existed on either side. The British rightly considered the New England states to be the birthplace of the Revolution, and the theory was that if they could isolate New England from the rest of the rebellious former colonies, they might be able to concentrate their forces and stamp out the rebellion piecemeal. At the very least, establishing a cordon around New England might have forced George Washington into attacking to break the cordon. Given superior British discipline, firepower, and potentially numbers, such a battle might well have led to the destruction of Washington’s main force; in that event American capitulation would likely have been merely a matter of time.

In the final act of the War, General Cornwallis dashed across Virginia in an example of what a British force could accomplish if it cut loose from its logistical tail. Unfortunately for Cornwallis, the French Navy for once achieved local superiority over the Royal Navy, and Cornwallis found himself with his back to the York River. He was forced to slaughter his horses to preserve his very limited stocks of food, and his troops were weakened by the effects of malaria. With no relief in sight, a dwindling force, and a growing American-French force pounding his defenses, Cornwallis was forced to surrender, and the Crown was forced to the negotiating table.

In the final act of the War, General Cornwallis dashed across Virginia in an example of what a British force could accomplish if it cut loose from its logistical tail. Unfortunately for Cornwallis, the French Navy for once achieved local superiority over the Royal Navy, and Cornwallis found himself with his back to the York River. He was forced to slaughter his horses to preserve his very limited stocks of food, and his troops were weakened by the effects of malaria. With no relief in sight, a dwindling force, and a growing American-French force pounding his defenses, Cornwallis was forced to surrender, and the Crown was forced to the negotiating table.

Having said all that, combat in North America was different from combat in Europe. In the Americas distances were greater, troops less numerous, the ground more broken, and cavalry less prevalent. These factors forced commanders on both sides to adapt their tactics: there is compelling evidence that units on both sides adopted open formations, with up to a yard between soldiers, and also employed double, rather than triple lines. These adaptations made formations less vulnerable to incoming fire and enabled them to cover more ground. At Bunker (Breed’s) Hill in 1775, for example, the British used tight formations and attempted to trade volleys with the American militia, who fought from behind breastworks. As a result they suffered staggering casualties. They also learned to rely on bayonet charges. Their third attack at Bunker Hill was carried out with bayonets only, and succeeded. The British took this lesson to heart.

Having said all that, combat in North America was different from combat in Europe. In the Americas distances were greater, troops less numerous, the ground more broken, and cavalry less prevalent. These factors forced commanders on both sides to adapt their tactics: there is compelling evidence that units on both sides adopted open formations, with up to a yard between soldiers, and also employed double, rather than triple lines. These adaptations made formations less vulnerable to incoming fire and enabled them to cover more ground. At Bunker (Breed’s) Hill in 1775, for example, the British used tight formations and attempted to trade volleys with the American militia, who fought from behind breastworks. As a result they suffered staggering casualties. They also learned to rely on bayonet charges. Their third attack at Bunker Hill was carried out with bayonets only, and succeeded. The British took this lesson to heart.